Pelin Esmer’s documentary The Collector [Koleksiyoncu] (2002) follows an individual with a very particular pastime through the busy streets of Istanbul. The main character and narrator, an old man whose name is never revealed, is a collector of all kinds of objects. Shake powered flashlights, newspapers, rosaries, stickers from fruits, lists of the names of dead friends, glasses, fish bones, magazines, books, miniature kitchen utensils, among many, are some of the objects that the collector hosts in his apartment. While the house of the Collector could be easily associated with a hoarding disorder, the documentary does not focus entirely in the malaise of collecting objects, but rather in the unexpected happiness of gathering and piling objects.

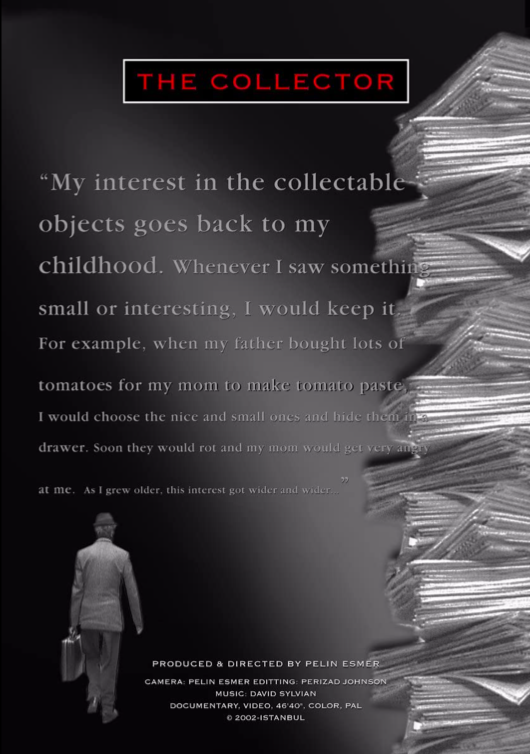

“My interest in the collectable objects goes back to my childhood. Whenever I saw something small or interesting, I would keep it. For example, when my father bought lots of tomatoes for my mom to make tomato paste, I would choose the nice and small ones and hide them in a drawer. Soon they would rot and my mom would get very angry at me. As I grew older, this interest got wider and wider…” says the main character and narrator of the documentary, and so does the poster that promotions the documentary. While tomatoes go bad after being kept, the objects that the mature collector keeps in his apartment are all things whose damage, or malaise, comes from the space they use. As the Collector acknowledges, he only keeps things that won’t damage other things. The piling of objects day by day grows and it is harder to live or move in the apartment. With the hope of finding a place for all his precious newspapers, the main character finds a university who might receive them all without having to recycle them or dispose them. The Collector does not recycle, does not throw away, does not forget any object, does not lend any piece, he sometimes gives away what he has, but besides he keeps his collection as if he were nurturing a son, so says the Collector himself.

The noise and vividness of the streets of Istanbul don’t stop. As the Collector wanders the camera follows him to all kind of markets, bazars, corner stores, restaurants, coffeehouses. Everyone buys, everyone consumes. In a way, the Collector is like any other consumer, he buys what he thinks he wants and tries to outsmart the market by buying always in pairs: one for the collection and one to use. Collecting becomes more than piling objects but less than archiving. “To be honest, I cannot claim that this is the aim behind my collections, being a bridge between yesterday and tomorrow is not the overriding idea for me. I see collections as a hobby not as a mission” (41:30). It is not a work, and yet occupies the Collector’s day completely. It is a hobby that looks like a job.

Collecting, in a way, is an addiction, as put it by the old man himself, “Making collection is a sickness without a cure.” Like an addict, the one who collects is also like a slave. “We can call this a ‘voluntary submission’, or even a ‘mandatory submission’” says again the old man. His duty consists in keeping things in a safe place, things that, like the newspapers, will paradoxically sabotage the very basis of his daily life in his apartment. At the same time, says the old man “the worst thing is, I don’t really feel like fighting against it. I know it is necessary, I need to find a solution but, I just let it take its course” (42:35).

What would happen with the collections after the Collector’s death? If the objects kept would find a way, ideally, they’ll be the trace of a particular existence. However, it seems the opposite. All that could happen to the collections after their keeper’s death is beyond the keeper’s power. “Collections are a way of clinging to life” says the old man in the final sequence of the documentary. If collecting was the mean that allowed existence to cling itself to life, then without collections life would be like the empty house of the Collector, as he imagines it, “a very dull place.” Without objects, life loses its liveliness. Without collections, where would liveliness find its colours? Without addiction how would existence cling to life and the other way around?